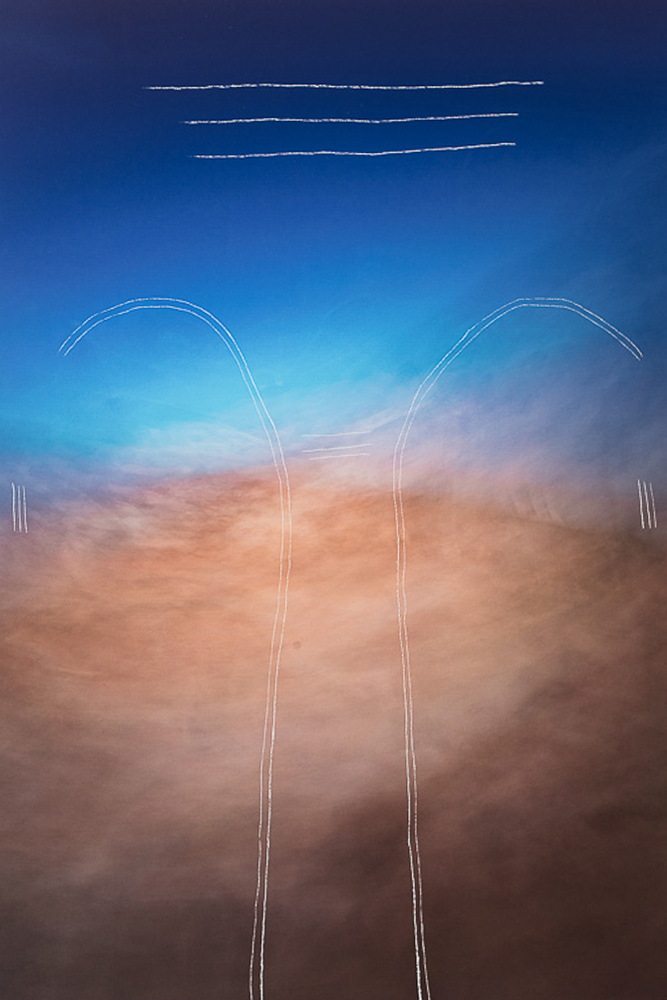

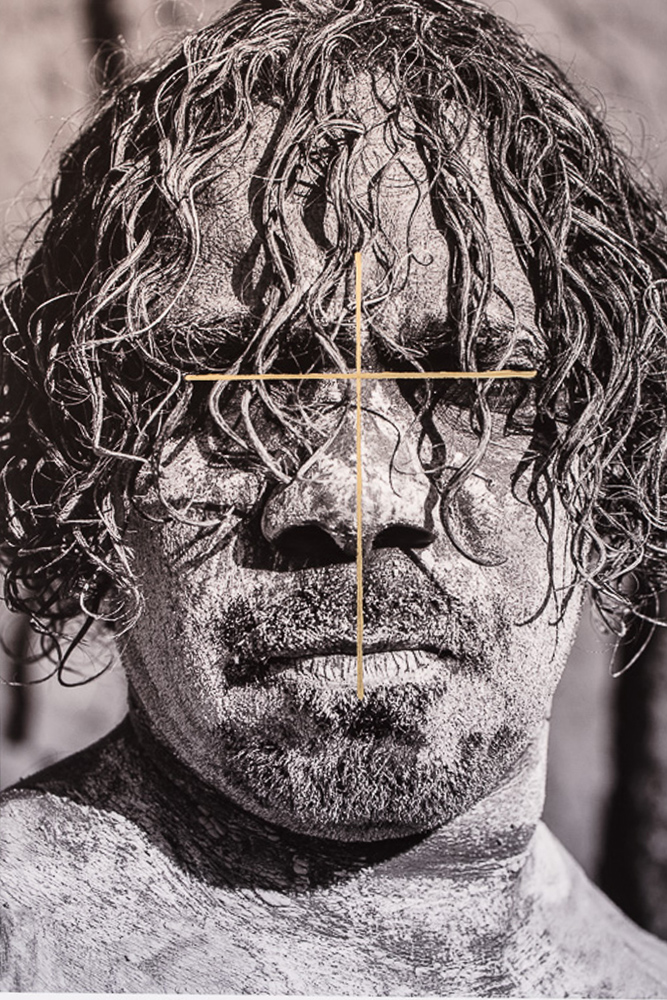

The exhibition ‘Scar’ is about delving beneath the surface of the stories behind the images. The artist physically scars the paper to create the works, which is a slow, meditative process. They work with personal experiences, those relating to the region in which they live, and at a national level. They try to keep things simple and do as much work in-camera as possible to maintain a connection to the moment. Finding the right subjects can be difficult, but it is important to have people telling the right stories. The isolation of living in a remote area has helped the artist develop their unique style. They use familiar visual language to subvert the viewer’s expectations and open their minds to the stories they are telling. They hope to give the viewer a history lesson while creating beautiful images.

Canson Art Rag

A1 Edition of 1 SOLD

Museo Portfolio

Editon of 5 in A1 size

Canson Art Rag

A1 Edition of 1 SOLD

Museo Portfolio

Editon of 5 in A1 size

Canson Art Rag

A1 Edition of 1 SOLD

Museo Portfolio

Editon of 5 in A1 size

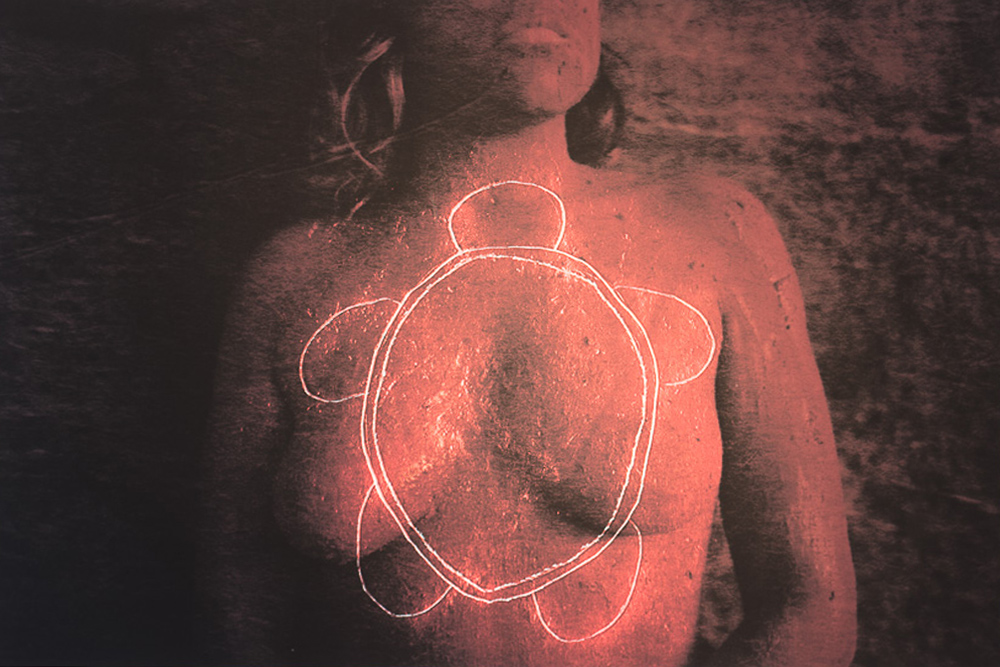

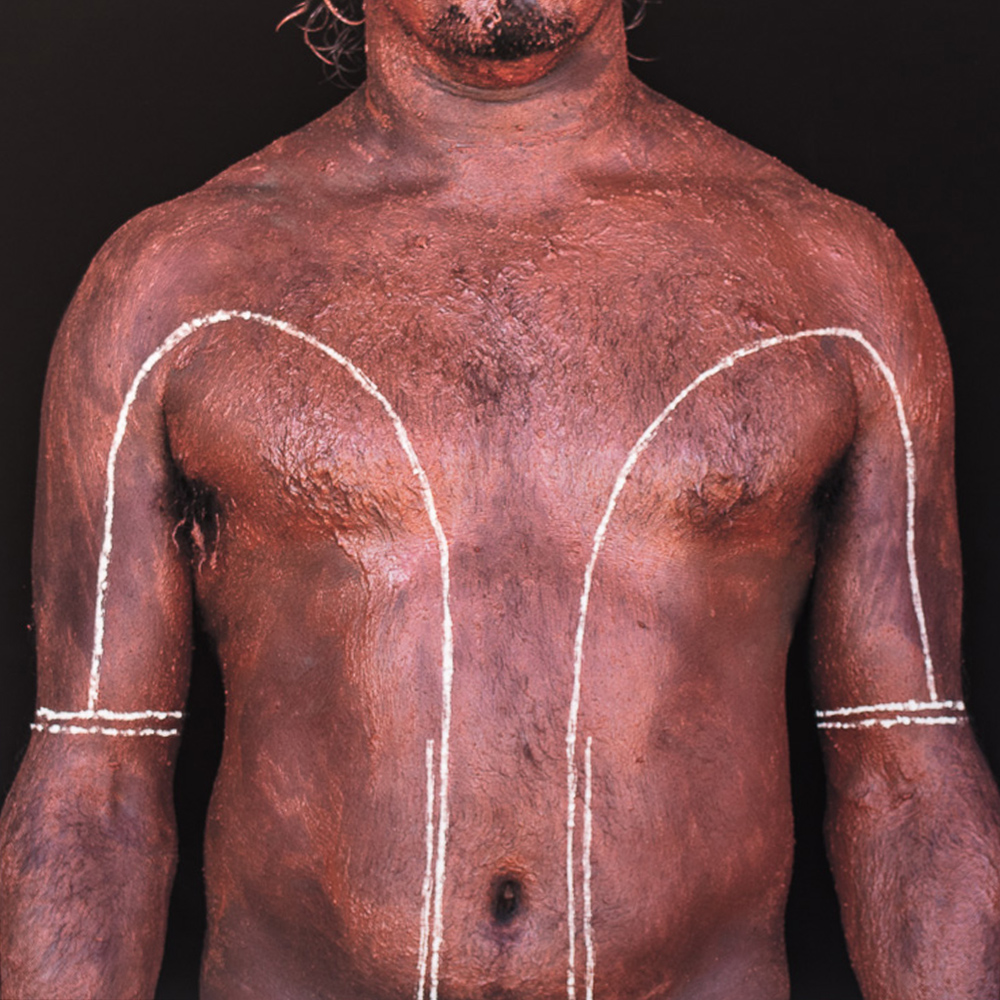

Torres identifies as a Yawuru and Djugan man and grew up with the art of pearl shell carving, a custom he said was dying out.

Canson Art Rag

A1 Edition of 1

Museo Portfolio

Editon of 5 in A1 size

Canson Art Rag

A1 Edition of 1 SOLD

Museo Portfolio

Editon of 5 in A1 size

Canson Art Rag

A1 Edition of 1

Museo Portfolio

Editon of 5 in A1 size

He was inspired by this and other scarification techniques, including those made on the skin during initiation ceremonies and has re-imagined them in his exhibition Scar.

“I wanted to use photography as one way of bringing back those concepts,” he said.

Canson Art Rag

A1 Edition of 1

Museo Portfolio

Editon of 5 in A1 size

Canson Art Rag

A1 Edition of 1 SOLD

Museo Portfolio

Editon of 5 in A1 size

Canson Art Rag

A1 Edition of 1 SOLD

Museo Portfolio

Editon of 5 in A1 size

He had to overcome social and community barriers to attract photographic subjects from his home town, where he |painted their chest areas, then scratched the surface of the printed photo.

Short explanations accompany the works, which cover issues such as suicide and oppression.

Canson Art Rag

Edition of 1 SOLD

Museo Portfolio

Editon of 5

Canson Art Rag

Edition of 1

Museo Portfolio

Editon of 5

Canson Art Rag

Edition of 1 SOLD

Museo Portfolio

Editon of 5

Canson Art Rag

Edition of 1 SOLD

Museo Portfolio

Editon of 5

“As I was doing it I thought more about trauma as a type of scar,” he said. “Peel the layer of beauty off and you see the trauma beneath it.”

Creating the pieces was an emotional process for Torres.

“When you think about some of the stories of the work as you start cutting into the paper, it did bring up a lot of emotions inside I didn’t realise I had,” he said.

Canson Art Rag

A1 Edition of 1

Museo Portfolio

Editon of 5 in A1 size

“It was quite meditating, it was a strange moment.”

He describes his artwork as subtly political and hopes people will feel inspired to learn more about indigenous people and history, though noted it was pertinent to all. “It’s not just one people’s story, we all have had trauma in our own lives,” he said.

Torres became interested in photography in 2012 and found his niche just two years ago and since then has been part of three group exhibitions in Perth and Sydney.

Canson Art Rag

A1 Edition of 1

Museo Portfolio

Editon of 5 in A1 size

Canson Art Rag

A1 Edition of 1

Museo Portfolio

Editon of 5 in A1 size

Canson Art Rag

A1 Edition of 1 SOLD

Museo Portfolio

Editon of 5 in A1 size

At age 40, he is disappointed it has taken him this long to find his passion but now has a sharp focus.

He hopes to expose other indigenous art forms other than painting and encourage their mainstream acceptance.

- Community News Story

- RTR Interview

SCAR II

Building on a successful debut solo exhibition, Michael Jalaru Torres presents ‘Scar II’.

This intimate series of photographic works showcases modern and traditional stories of the connection between people, the country and the past.

Capturing the vibrant colours of the landscape and the raw emotion of his people, Michael explores Australia’s first peoples’ language of design, oral histories and legacy of trauma and loss.

His images incorporate line-work and patterns which reflect traditional lore and practices of marking the landscape, objects and the skin. Scarification and carvings on wood and shell are timeless markings which speak of songlines.

Today new markings are made with inks, pigments, metal and digital code.

This reveals the contemporary life of

Michael’s images tell a powerful story of the scars which mark people and the land. The exhibition is about getting under the surface, scraping away the layers to get to the story.

Generations of Australia’s first people have scarred skin for lore, while carving wood, stone and shell for hunting and ceremony. They have witnessed nature’s shaping of country while experiencing other men’s hunger to scar the country for wealth.

Lines and markings have created a unique visual language that coexists with oral history, songlines shared on country, and a cultural connection from before time to present day. Adapting and surviving through colonisation, the new scars of survival are more often hidden from plain sight.

What was the idea behind the exhibition?

The whole thing about ‘Scar’ is getting under the surface, scraping away the surface to get to the story. And that works with the conceptual idea of it, as well as the visual idea, where I’m actually physically scarring the paper.

That act of physically scratching back into the paper, it must be quite difficult to make the first mark.

It takes hours, sometimes days.

I’m 2000 kilometers away from my printer, and it costs so much and takes time. You go through it in your head, sketch it on paper, check that your hands aren’t shaking too much.

You go through all that process and then put blade to paper.

It’s good to get that instant satisfaction from photography, but I also get that meditative state of making art when I’m scarring the paper, and my mind starts wandering.

It becomes very emotional and opens you to things in the past and then it is pretty confronting. Doing that kind of scarring made me see why people use art as a way of healing because the act of slowing down is amazing.

How would you describe your process?

I work on experiences that are personal, or experiences which relate to the region which I live in, as well as relating to the national level.

I’m in this great location in Broome and the Kimberleys.

I’m trying to create everything in that environment, on location, and to work with people who are connected to stories in the area.

I try to do as much of my work in-camera, instead of completing composition in photoshop, which forces me to keep it simple and be very practical. I find that process challenging, but also a bit more free.

If you rely on editing everything in the computer it can take away from the experience of creating images.

There’s immediacy to your process as well, working in-camera, there’s a connection to the moment that the image was made.

A lot of my work is a deeply rooted emotional experience.

I try to capture people, and capture them at that moment.

And then show them the preview on the back of the camera and get that connection straight away, as opposed to shooting in a studio and editing it. In a way it’s taking the Hollywood out of it. Just paring it back.

What is your approach to finding and working with models or subjects?

Well trying to find subjects is the hard part. Finding the design and the stories that I want to portray is quite easy in a way. But actually getting the people who are connected to the story, or visually relevant to the design, can be difficult where I live.There’s a lot of walls to break through just to get that shot sorted. Which makes it harder but also more rewarding.

People are proud of seeing their story told, and also seeing that someone has connected with Indigenous storytelling. You’ve got to have the right people telling the right stories.

And your role becomes important, because it’s your story to tell as well.

I guess some of it’s my story, but then it’s also someone else’s. My family wasn’t directly involved in the Stolen Generation, but I’ve had some of my extended family involved. I’ve found other people who were deeply affected, and then asked their permission to be in the story and tell their side of it, or their family’s side of it. It’s kind of a collaboration in that regard. And although it never really affected me personally, we’re all affected by it in some way.

How does living in a place like Broome, which is so far from the major capital cities, affect your art?

It’s is very isolated and there’s not a lot of opportunities to see interesting works in galleries or museums, so you rely on technology and screens. It’s good in way because you don’t get influenced too much.

I guess another good factor is the visual appearance of a lot of the people up this way.

There is a lot of diversity which is good for a photographer.

It’s a melting pot of cultures.

There’s a lot of influences I haven’t touch on yet, through the introduced cultures which aren’t deeply connected into the Indigenous cultures.

In saying all of that, being isolated I’ve had to rely on myself to figure things out and train myself in photography.

It’s a very difficult and unique challenge.

It sounds like you’ve been able to turn the isolation into a positive, in terms of being self-reliant but also because the place itself is beautiful and interesting.

People can romanticise the landscape and purely do landscape photography.

So for me to get out of that and try and do conceptual works, either portraits, or abstract landscapes is scary in a way.

Especially because you’re going against the grain of what people want to see.

You’d be amazed how much people want to see a Boab tree on the landscape. It’s something that I guess that the rest of Australia, and the world, connect with the Kimberleys and is what they expect to see.

For me I’m trying to capture the unexpected, and draw the viewer in with the same beauty.

You know the same colours are there, the landscape is there, the strong characteristic people are there, but the story behind that image is deeply different to what they’re used to.

So you’re using parts of the visual language that they are familiar with, but then subverting it and showing them stories they’re not used to seeing?

There is a lot of stories that haven’t been told.

Exposing themes and history that happened around the Kimberleys can be too confronting some people.

So I’m trying to visually trick them to open their mind to those stories.

For me it’s creating beautiful images, and sucking the viewer into that, and giving them a history lesson in a way: about those designs, those people, that region.

I find that if you have something that is too confronting, people just walk by, they don’t want to connect for whatever reason.

And people tend to like visually pleasing things first, it draws them to it.

I want them to be fooled, in a way, then read about the art and walk away with hopefully a new understanding of those stories.

So that is the whole idea of making my work visually pleasing but there is the hidden message or the story that is not necessarily pleasing.

There seems to be a tension between the future and the past in your work.

You use high-end technology, but then you’re talking about traditions and the legacy of colonisation.

So how do you explore notions of time?

My work does contradict a bit, because I’m using the latest technology, but I’m using that technology in quite an old fashioned style.

Because of technology and the internet you can get feedback immediately.

Which is great, but goes against a lot of Indigenous thinking.

You know, where you don’t rush anything: you take your time, and experience the story that you’re telling.

‘It’ll be done when it’s done’ is kind of the mantra of Indigenous artists, because a lot of works, such as painting or carving, take time.

But with newer technologies it’s almost instant.

The other side is how our stories are shared with that technology.

Journalists and tourists go to our communities and towns taking photos of everything.

But in the western world people might take a photo of someone, in their community, and they don’t put any words to it, or the word don’t match the image.

And I guess that’s a barrier that need to be broken down, because a lot of people are wary of that.

People don’t necessarily trust where that image is going to go.

Because of the internet, people can now see traditions and stories which are not filtered through media outlets.

Through tattoos, jewellery, scarification, or just designs and colours on clothing, a lot of people in western culture now see the value of Indigenous designs.

The good side is the revitalisation of language to Indigenous communities and language groups.

I hope that my grandkids will be able to walk around this country and be able to see our designs and words around, even down to street signs and public art.

People can now see the importance of a design language which was almost taken away but is coming back.

A lot of those things were stripped away from Indigenous cultures when the major religions colonised the world.

You’ll find in my works, there’s stuff which people see as anti-religion. It’s not really.

It’s more about awakening people and exposing them to what’s happened in the past: how the system is corrupted and decimated a lot of cultures and ways of life.

What role do you think art has in healing from trauma and loss, particularly in relation to the effects of colonisation and the stolen generations?

Art is probably the most universal, or the most easily accessible way of healing.

A lot of mob, have to create art as a way of interpreting their emotional loss, and trying to reconnect.

Because it’s a slow process painting is kind of a meditative state.

Of course if you’re using newer technology you don’t really get into that meditative state, but you become distracted by that process. And when using technology you get that instant satisfaction, and people connect directly through comments and likes, which is a good way of getting affirmation, and showing people what you’re trying to expose.

So overall, what do you want the audience to take from your work? And does that message change based on whether they are Indigenous or non-Indigenous?

I guess it’s about my people feeling proud that another part of their story is being shown, and that we are evolving in our ways of art. It’s not just dot paintings on canvas. I’m definitely part of a wave that is pushing it.

For non-Indigenous people, the kick I get is when someone comes to the exhibition who doesn’t know anything about it.

They nod their head and say it’s pretty, and then they read the description of the images and do another lap but this time 10 times slower.

They look at the image and you can see a connection click in their head, and they become really quiet. Which is great because they are finding an individual connection to the images.

Michael Jalaru Torres would like to thank:

Sally Wilkinson, Jadaja Torres, Aimee Howard, Geraldine Henrici, Philippa Jahn, Jennifer Garland, Desert River Sea, Paper Mountain, Wanneroo Library and Cultural Central

Paper Mountain would like to thank their magnificent Gallery Attendants:

Ben Yaxley, Brooke Barker, Brooke Jones, Carolina Arsenii, Claire Taylor, Claudia Minutillo, Danyon Levi, Devan Job, Felicity Eustance, Gabby Loo, Hollie Clarkson, Jack Caddy, Karoline Forsberg, Laura Margaret, Madeline Sarich, Matthew Perrett, Natalie Blom, Nathan Tang Nathan Viney, Phoebe Mulcahy, Shannon Fae, Sharon White, Shauna Goh, Stephanie de biasi, Stephanie Gilhooley, Teresa Watts

Exhibition at Paper Mountain